I hadn’t been paying attention.

It didn’t register when, on Aug. 10, 2006, the Transportation Security Administration decided that gels, ointments, lotions, liquids and aerosols represented a potential danger and therefore should be intercepted and confiscated at airport security checkpoints.

It was summer. It was hot. I was working on a couple of stories about the failures of government. I mean, I really can’t be all things to all people.

Then, about six weeks later, on Sept. 26, the TSA relented. A little. Now it was permitting passengers to bring most gels, ointments, lotions, liquids and aerosols — so long as the quantity of each did not exceed three ounces, and so long as each three-ounce-or-less container of gel, ointment, lotion, liquid or aerosol was deposited in a transparent, sealable plastic bag.

At the time, I was working diligently on stories about violent crime and worker exploitation; I was struggling to get enough sleep what with the need to beat the 7:40 a.m. public school bell; I was still too hot and busy scratching my mosquito bites, so this TSA announcement, too, went unnoticed.

To my great peril.

For soon I would come to know first hand what it means to be a true security threat.

Charleston International Airport, June 11, approaching TSA officials after standing in line at the security checkpoint for 10 minutes. AirTran Airways, the “low-cost” Atlanta-based airline that recently added Charleston to its routes, provides a seductive online check-in option. Reservations can be made, seats selected, boarding passes with bar codes printed out, all in the luxurious comfort of your home office. Saves time. Puts you and your carry-ons in the security checkpoint line faster than you can say “Zacarias Moussaoui.”

“Anyone in line with liquids or gels?” the security guard says.

“What did she say? Liquids? Um, is whiskey a liquid?” I ask my wife.

“Well, it’s sealed, right?” she replies. “It’s in your bag?”

It’s in my bag, my carry-on bag, packed among the clothes, protected from the inside edge by various socks and covered carefully with tee shirts. It’s 5:55 a.m. Our flight leaves for Florida at 6:15 a.m. The line to get to the gate is long.

“Any liquids, creams or gels?” the guard asks again, looking at me.

“Um. I’ve got a wrapped gift of scotch for my father, does that count?”

“It’s staying here.”

For a moment I am flustered, an insufficient quantity of caffeine, now significantly diluted, courses through my bloodstream. I’m thinking, I really need another cup of coffee. I’m thinking, What’s the big deal? Surely a sealed, clear bottle of precious single-malt scotch isn’t really a liquid. It’s, well, scotch.

“Is it more than three ounces?” the security official asks.

“It’s a bottle… a gift… for my father… for Father’s Day…”

“It’s staying here,” she says.

“No it’s not!” I protest, with a certain futility I am beginning to recognize. “Why not open the box?” I posit. “You can see for yourself it’s sealed.”

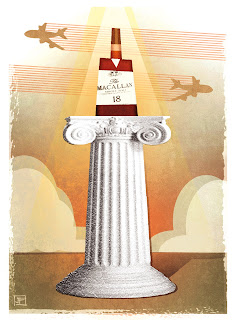

The scotch — a 12-year-old Macallan, aged in hand-picked sherry-seasoned oak casks from Spain — cost me 60 bucks and change. I am not about to make a gift of it to some lucky schmuck at the airport. I am not about to give it up. No way.

“You can try to check your bag,” another security guard suggests.

So I run, run like the wind, limping a little because of my sore foot and bad knee, my carry-on rolling behind me, the scotch sloshing inside.

Three women stand languorously at the counter with nothing to do. They are like perilous sirens perched on a sandbar, beckoning, promising nothing but disaster. I’m panting. I’m imploring them to take my bag, take it, take it away from me, please!

Too late, they tell me. One yawns. Another scrutinizes her fingernails. The computers are shut down, they say. No more bags can be checked.

The plane is scheduled to depart in 10 minutes. I huff. I puff. I start to speak… Then I’m thinking, Maybe I can find someone to hold my precious 60-dollar bottle of 12-year-old single-malt scotch whiskey for me while I’m away, you know, protect it, cradle it, admire it, store it in some safe unseen niche, and I can retrieve it upon my return. I run to the information desk. It’s 6:05 a.m. and no one is there. And I’m thinking, The return flight lands at the Charleston International Airport round midnight… Who would still be here at that hour? Who exactly could guard my precious 60-dollar bottle of 12-year-old single-malt scotch whiskey? Who might I rely on? I see no one. I can think of no one. I run down the hall, past the newsstand, back to the security checkpoint.

I confront another TSA officer. I am now desperate.

“Is there anyone who can keep the bottle safe for me while I’m away?” I ask him, knowing full well the rhetorical nature of my question.

A silent response: He shakes his head.

That’s when I curse.

“I would rather miss my #%&$! flight than give up my precious 60-dollar bottle of 12-year-old single-malt scotch, aged in hand-picked sherry-seasoned oak casks from Spain!” I scream.

“Watch your language,” the TSA officer says tersely.

Meanwhile, my wife and daughter have proceeded to the gate, boarded the plane. They don’t know my status. They don’t know if I’m coming or not. They are dismayed, distraught, discombobulated, disturbed. They have been dissed.

I have been dissed. I’m thinking, Who in his right mind could possibly take away a man’s bottle of precious single-malt scotch whiskey? It’s inconceivable. Well, it should be inconceivable, just as parting from my precious bottle of scotch is inconceivable to me.

And then I’m thinking about how silly this ban on gels, ointments, lotions, liquids and aerosols is. I mean, three ounces is OK, but 3.1 poses a threat? I can buy a bottle of water from a vendor just the other side of the security checkpoint and bring it onto the plane, but I have to give up the bottle of water I’m drinking now? I can get airport officials to load containers of gels, ointments, lotions, liquids and aerosols in the luggage compartment beneath my feet, but I can’t stow containers of gels, ointments, lotions, liquids and aerosols under the seat in front of me?

I mean, aren’t bombs usually detonated remotely?

And then I’m thinking about how removed I am from the world’s conflicts, from suicide bombings and neo-colonial catastrophe. I’m thinking about how successful the terrorists are in Iraq, how an average of 100 Iraqis are dying each day, how dozens of American soldiers are being killed each week. I’m thinking about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the moral, spiritual and physical devastation it has wrought over the decades. I’m thinking about the poor in New Orleans and how they have been betrayed, how their right to a secure life has been denied. I’m thinking of people here in Charleston, struggling to survive.

I’m trying to figure out what, exactly, “homeland security” means.

It’s 6:15 now. It’s too late. I’ve lost the flight.

I wake my parents in Florida to explain the situation. Not very thoughtful of me, I know, I know.

I calm down. The fatalist in me is reconciled. I am here. I need to get there. I have a rolling bag with a bottle of scotch inside it.

I return to the three sirens. Calmly, I ask if they can put me on the next flight. They can. They are kind now, though still disinterested. They tell me to return at 9 a.m. to check in — to check my bag — to leave sufficient time to get through security.

I kill time. My wife calls from the stopover in Atlanta and I explain. I call my parents back. I tell them I leave Charleston at 10:30 a.m. I leave Atlanta at 3 p.m. I arrive in Florida at 4:30 p.m. It takes about 40 minutes to get to the house from the airport. We’ll be there in time for the cocktail hour, I assure my father.

Much, much later I am in Florida. My wife and daughter have been there since 9:45 a.m. My father makes his second trip to the airport.

As he pulls out of his driveway he rolls down his car window to make an announcement.

“I’m going to get my scotch,” he says.

Adam Parker

July 8, 2007

Saturday, July 02, 2011

Dread Takes Several Forms

Dread takes several forms. It offers us an emotional range that begins with something slightly more acute than mere dislike and extends to a paralyzing fear of death.

Of course, death is at the bottom of it. Should we find ourselves disconcerted by the arrogant swagger of a grimy man in a loose-fitting overcoat making his way through an enclosed space, it could be because we think it’s possible he will pull out a long gun and spray the room with buckshot. If looking in the mirror we are repelled by a new abundance of gray hairs, or if we sense a collapsing vertebra as we walk the dog, it might be because such developments signify that we are a step or two closer to the abyss.

Tonight, though, dread came unexpectedly, and not because I feared my own demise. No, my dread—my wide-eyed moment of horror—was provoked by my 9-year-old daughter, Zoe, who I could see had, for the first time, truly comprehended the nature of mortality. Probably it was not a conscious awareness, a concrete thought in her mind that revealed the black beyond, but undoubtedly the shock and fear she expressed after a simple joke went mildly awry only could have been the reaction of someone whose life experience had just expanded enough to include a clear sense of the finite. It is a small trauma to recognize in one’s young child a nascent ability to recognize death—to recognize it and to fear it.

It was bedtime. I was lying next to her preparing to read a little from a collection of folk tales by Hans Christian Andersen. As usual, we were jostling, tickling one another, laughing, and throwing stuffed animals around before she settled down for deep sleep.

I placed her alarm clock at a distant corner of the small table in her room and joked that this would force her to get out of bed to turn it off when it beeped at 6:30 in the morning, an hour we both resented with all our might, but which demanded our respect lest the school bell beat us to the punch.

“Noooo, Dad, please,” she said, trying to get out of bed.

I told her I could probably reach it.

“Without touching the floor,” she said admonishingly.

I stretched, I reached, I quickly understood I would need to prop myself up with one arm while extending the other toward the clock. I gripped the bed frame with my right hand and moved the other hand across my body, my torso hanging over the edge. Of course I lost my balance and, with a thump and a smile, landed, back down, on the floor, narrowly missing the rounded corner of a little wooden commode.

Zoe froze with fear, managed to ask me if I was OK, then burst into tears and rushed to embrace me. Quickly I assured her I was fine, that the fall was not profound, that no pain was associated with it and that this was only a joke.

“But I thought you hit that corner,” she said, gasping. She thought I was injured; she thought my health, my wellbeing, my life was in danger. She had glimpsed an inevitably lonely future. Back on the bed, I reassured her. She snuggled close, placing her head on my breast. This is when I realized what had really happened. This is when the dread set in.

Nine years ago, when Zoe was born, our joy was overwhelming. It was a difficult pregnancy, and parenthood had been very much in question for several years. That our daughter emerged into the world was miraculous enough, but her beauty and fine temperament only added to our bliss.

But every bliss, in order to be bliss, must contain a note of dread. Ecstasy, as the sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini knew so well, is what one feels the moment love’s arrow pierces the flesh, the consuming sensation whose ingredients include agony, like water so scalding it momentarily feels cold to the touch.

I remember the day soon after Zoe’s birth, before she could sleep through a night, when guilt and pain set in, for I realized I was partly responsible not only for what happiness and success my daughter might achieve in her life, but for any distress she might endure, for certain inevitable disappointments, for unavoidable suffering—and, ultimately, for her death.

I was especially mortified not at the idea that she would one day die, but that I would surely die so much sooner, that I would not be there to help her, to hold her, to try to comfort her, to love her. Oh cruel trick! To grant someone life only to abandon her in her time of greatest need! It is a thought I still cannot bear.

And lying in her bed, with the thick tome of folk tales resting on my gut, my worst fear was partly realized. My daughter, so full potential—her life still at its beginning, her thoughts enlarging, her awareness growing, her confidence blooming—my 9-year-old daughter was, in a sense, already beginning to die. True, she could not yet see the end, or imagine it with the calm rationale of a satiated materialist. But she now knew of the end, and that her path inexorably would take her there.

Awareness of a process tends to set it in motion. For a father, who can travel with his daughter only part of the way, this is no easy matter. It fills me with dread.

Adam Parker

Jan. 6, 2010

Of course, death is at the bottom of it. Should we find ourselves disconcerted by the arrogant swagger of a grimy man in a loose-fitting overcoat making his way through an enclosed space, it could be because we think it’s possible he will pull out a long gun and spray the room with buckshot. If looking in the mirror we are repelled by a new abundance of gray hairs, or if we sense a collapsing vertebra as we walk the dog, it might be because such developments signify that we are a step or two closer to the abyss.

Tonight, though, dread came unexpectedly, and not because I feared my own demise. No, my dread—my wide-eyed moment of horror—was provoked by my 9-year-old daughter, Zoe, who I could see had, for the first time, truly comprehended the nature of mortality. Probably it was not a conscious awareness, a concrete thought in her mind that revealed the black beyond, but undoubtedly the shock and fear she expressed after a simple joke went mildly awry only could have been the reaction of someone whose life experience had just expanded enough to include a clear sense of the finite. It is a small trauma to recognize in one’s young child a nascent ability to recognize death—to recognize it and to fear it.

It was bedtime. I was lying next to her preparing to read a little from a collection of folk tales by Hans Christian Andersen. As usual, we were jostling, tickling one another, laughing, and throwing stuffed animals around before she settled down for deep sleep.

I placed her alarm clock at a distant corner of the small table in her room and joked that this would force her to get out of bed to turn it off when it beeped at 6:30 in the morning, an hour we both resented with all our might, but which demanded our respect lest the school bell beat us to the punch.

“Noooo, Dad, please,” she said, trying to get out of bed.

I told her I could probably reach it.

“Without touching the floor,” she said admonishingly.

I stretched, I reached, I quickly understood I would need to prop myself up with one arm while extending the other toward the clock. I gripped the bed frame with my right hand and moved the other hand across my body, my torso hanging over the edge. Of course I lost my balance and, with a thump and a smile, landed, back down, on the floor, narrowly missing the rounded corner of a little wooden commode.

Zoe froze with fear, managed to ask me if I was OK, then burst into tears and rushed to embrace me. Quickly I assured her I was fine, that the fall was not profound, that no pain was associated with it and that this was only a joke.

“But I thought you hit that corner,” she said, gasping. She thought I was injured; she thought my health, my wellbeing, my life was in danger. She had glimpsed an inevitably lonely future. Back on the bed, I reassured her. She snuggled close, placing her head on my breast. This is when I realized what had really happened. This is when the dread set in.

Nine years ago, when Zoe was born, our joy was overwhelming. It was a difficult pregnancy, and parenthood had been very much in question for several years. That our daughter emerged into the world was miraculous enough, but her beauty and fine temperament only added to our bliss.

But every bliss, in order to be bliss, must contain a note of dread. Ecstasy, as the sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini knew so well, is what one feels the moment love’s arrow pierces the flesh, the consuming sensation whose ingredients include agony, like water so scalding it momentarily feels cold to the touch.

I remember the day soon after Zoe’s birth, before she could sleep through a night, when guilt and pain set in, for I realized I was partly responsible not only for what happiness and success my daughter might achieve in her life, but for any distress she might endure, for certain inevitable disappointments, for unavoidable suffering—and, ultimately, for her death.

I was especially mortified not at the idea that she would one day die, but that I would surely die so much sooner, that I would not be there to help her, to hold her, to try to comfort her, to love her. Oh cruel trick! To grant someone life only to abandon her in her time of greatest need! It is a thought I still cannot bear.

And lying in her bed, with the thick tome of folk tales resting on my gut, my worst fear was partly realized. My daughter, so full potential—her life still at its beginning, her thoughts enlarging, her awareness growing, her confidence blooming—my 9-year-old daughter was, in a sense, already beginning to die. True, she could not yet see the end, or imagine it with the calm rationale of a satiated materialist. But she now knew of the end, and that her path inexorably would take her there.

Awareness of a process tends to set it in motion. For a father, who can travel with his daughter only part of the way, this is no easy matter. It fills me with dread.

Adam Parker

Jan. 6, 2010

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)